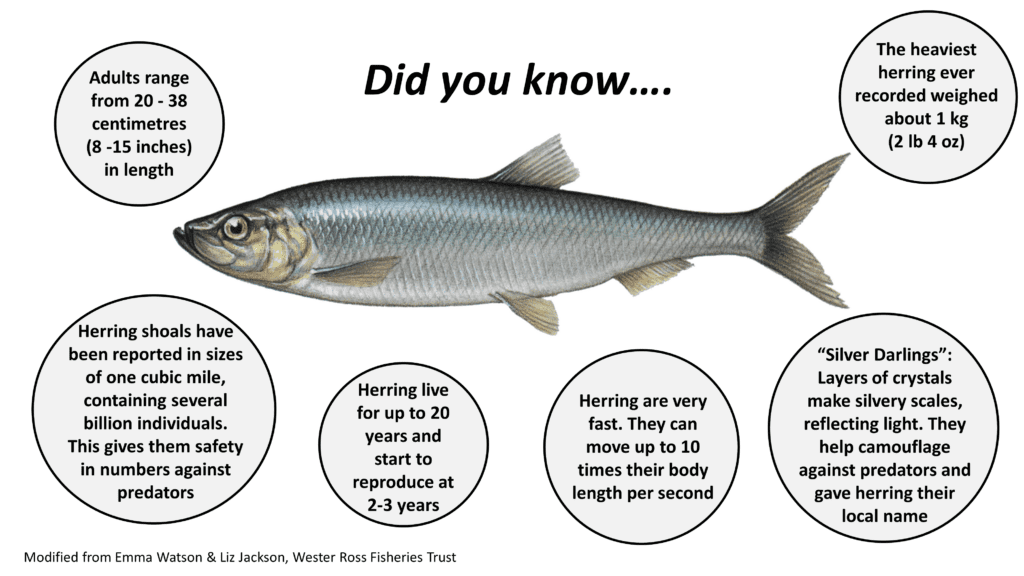

Atlantic herring (Clupea harengus) are an abundant fish, occurring on both sides of the Atlantic. They play a central role in helping to transfer energy from species lower in the marine food web to the larger fish that prey on them. Herring feed on small zooplankton, such as copepods and amphipods, krill, and fish larvae [2, 3]. Herring shoals attract predators, which include cetaceans [4-6], seabirds (e.g. gannets) [5], gadoids (cod, hake etc.) [6-8] and humans. Haddock, sand eels and cod also eat the eggs (and larvae) of herring [7].

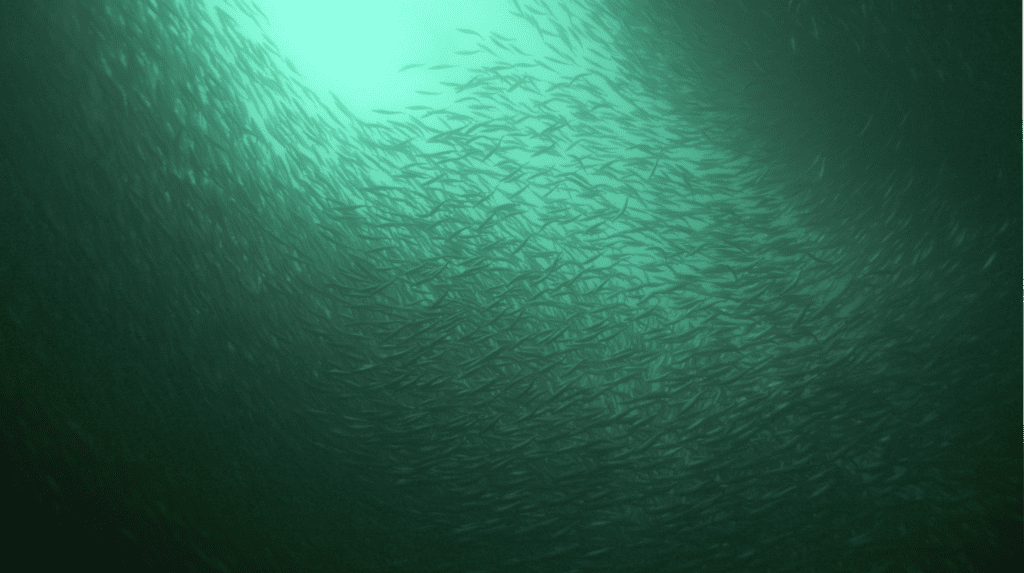

Atlantic herring form large schools. These are highly synchronised and fast-moving, allowing the fish to make sophisticated escape maneuvers [9]. Schooling behaviour can start as early as the larval stage [10-12]. It decreases the risk of predation to individual fish by improved predator detection and deterrence [9].

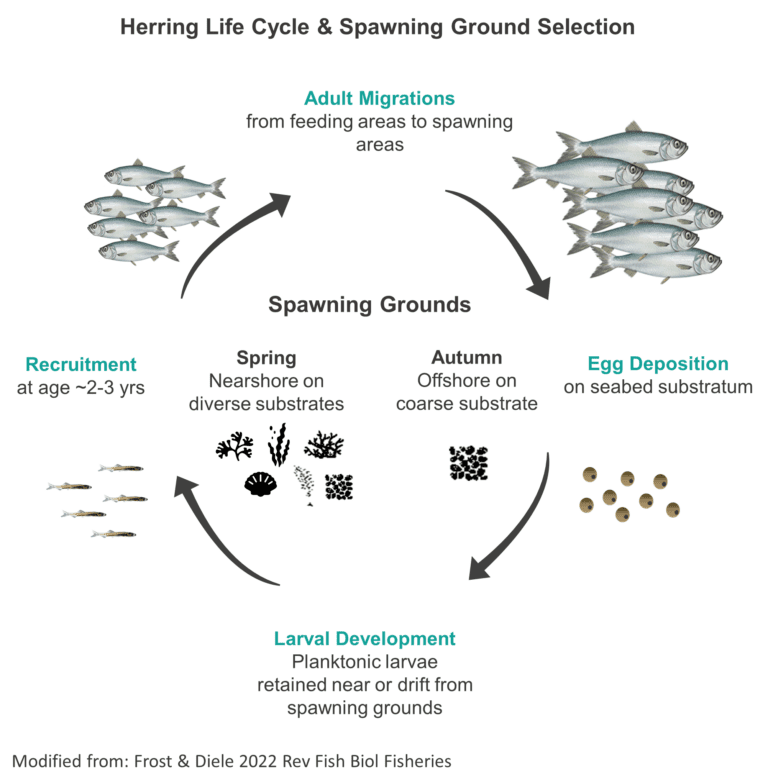

Schools migrating to spawning locations are densely packed and fast moving. The maturity of individuals in schools can vary from pre-spawning stage to resting stage at the same spawning site [13]. Single spawning schools have been observed splitting into pelagic (mostly in mid-water or upper layers of the ocean) and demersal (mostly in deeper layers of the ocean) groups [12]. After spawning, feeding becomes the priority, and herring form smaller, less dense schools near the surface [13-15].

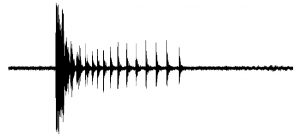

Herring can hear: their “ears” have thin air-filled tubes that project from the swim bladder to air chambers, connected with the inner ear [11]. There is evidence that they can hear the ultrasonic clicks emitted by cetaceans [16]. They can also hear sounds made by other herring [17]. They produce distinctive bursts of pulses called Fast Repetitive Tick (FRT) sounds, aka FaRTs [17]. The discoverers of the herring FRTs, including researchers from the Scottish Association for Marine Science, were awarded an Ig Nobel award in Biology. FRTs are thought to be produced by gas released from the swim bladder via the anal duct. As herring also shoal in the dark, it is possible that FRTs are used as “contact calls” between individuals within schools. The number of FRT’s released increases with school size and may be important to their social behaviour [17]. Whilst FRT’s can’t be heard by most predatory fish (2 kHz), cetaceans can still locate FRTing herring through echolocation.

Herring FRTs can also be detected by submarines, which almost led to a serious diplomatic crisis in 1982 when the Swedish Navy thought Soviet nuclear submarines were in Swedish waters. However, after a decade of fruitless pursuits, Sweden discovered it wasn’t the noise of submarines, but of large shoals of FRTing herring that they were recording.

Read more about herring Spawning Ecology, Fisheries, the WOSHH project, or find Resources.

Banner image: Shoaling herring. © Andy Jackson, SubSeaTV; reproduced with permission. Herring drawing: © Carl-Werner Schmidt-L

[1] Hunter A, Speirs DC, Heath MR (2019) Population density and temperature correlate with long-term trends in somatic growth rates and maturation schedules of herring and sprat. PLoS One 14:e0212176. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0212176

[2] Dickey-Collas M, Van Beek DFA, Wot H, Voor Visserijonderzoek C (2004) The current state of knowledge on the ecology and interactions of North Sea Herring within the North Sea ecosystem

[3] Cunningham JT (1896) The Natural History of the Marketable Marine Fishes of the British Islands. The MacMillan Co. New York.

[4] Macleod K, Fairbairns R, Gill A, et al (2004) Seasonal distribution of minke whales Balaenoptera acutorostrata in relation to physiography and prey off the Isle of Mull, Scotland. Mar Ecol Prog Ser 277:263–274. https://doi.org/10.3354/meps277263.

[5] Benoît HP, Rail J (2016) Principal predators and consumption of juvenile and adult Atlantic Herring (Clupea harengus) in the southern Gulf of St. Lawrence. DFO Can. Sci. Advis. Sec. Res. Doc.

[6] Jourdain E, Vongraven D (2017) Humpback whale (Megaptera novaeangliae) and killer whale (Orcinus orca) feeding aggregations for foraging on herring (Clupea harengus) in Northern Norway. Mamm Biol 86:27–32. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mambio.2017.03.006

[7] Høines ÅS, Bergstad OA (1999) Resource sharing among cod, haddock, saithe and pollack on a herring spawning ground. J Fish Biol 55:1233–1257. https://doi.org/10.1006/jfbi.1999.1122

[8] Speirs DC, Guirey EJ, Gurney WSC, Heath MR (2010) A length-structured partial ecosystem model for cod in the North Sea. Fish Res 106:474–494. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fishres.2010.09.023

[9] Pitcher TJ, Parrish JK (1993) Functions of shoaling behaviour in teleosts. In: Pitcher TJ (ed) The behaviour of teleost fishes, 2nd edn. Croom Helm, London, p 364–439

[10] Breder CM Jr (1976) Fish schools as operational structures. Fish Bull US 74:471–502

[11] Blaxter JHS, Hunter JR (1982) The Biology of the Clupeoid Fishes. Adv Mar Biol 20:1–223. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0065-2881(08)60140-6

[12] Axelsen BE, Nottestad L, Ferno A, et al (2000) “Await” in the pelagic: Dynamic trade-off between reproduction and survival within a herring school splitting vertically during spawning. Mar Ecol Prog Ser 205:259–269. https://doi.org/10.3354/meps205259

[13] Nøttestad L, Aksland M, Beltestad A, Fernö A, Johannesen A, Misund OA (1996) Schooling dynamics of Norwegian spring spawning herring (Clupea harengus) in a coastal spawning area. Sarsia 80:277–284

[14] Skaret G, Nøttestad L, Fernö A, et al (2003) Spawning of herring: Day or night, today or tomorrow? Aquat Living Resour 16:299–306. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0990-7440(03)00006-8

[15] Stacey NE, Hourston AS (1982) Spawning and feeding behaviour of captive Pacific herring (Clupea harengus pallasi). Can J Fish Aquat Sci 39:489–498

[16] Wilson B, Dill LM (2002) Pacific herring respond to simulated odontocete echolocation sounds. Can J Fish Aquat Sci 59:542–553. https://doi.org/10.1139/f02-029

[17] Wilson B, Batty RS, Dill LM (2004) Pacific and Atlantic herring produce burst pulse sounds. Proc R Soc B Biol Sci 271:95–97. https://doi.org/10.1098/rsbl.2003.0107

Email: [email protected]